Stephen-vb Fotografie

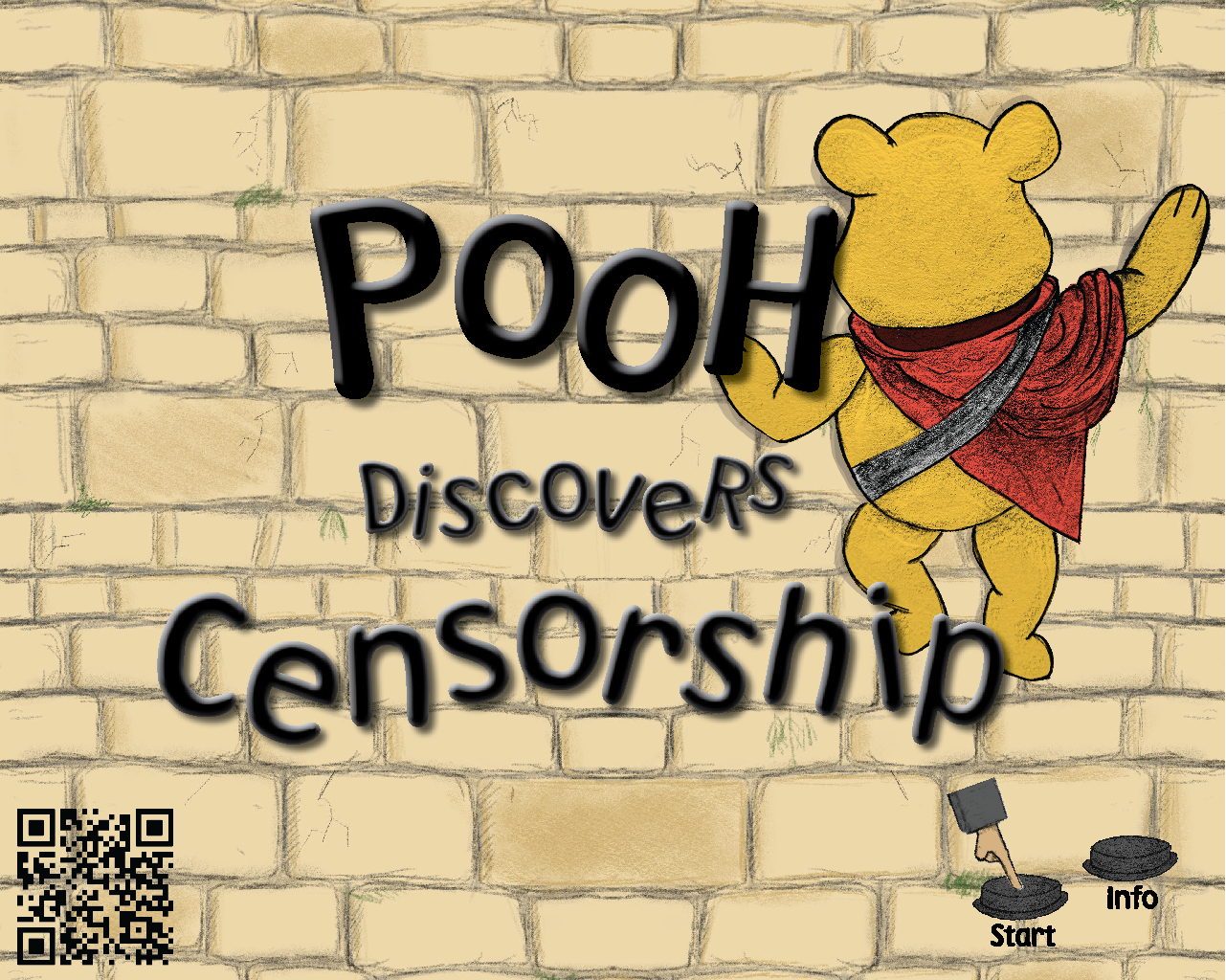

Team Pooh:

Thijs Kissen

Floor Faes

Ivo Hobbelen

Lars Holm

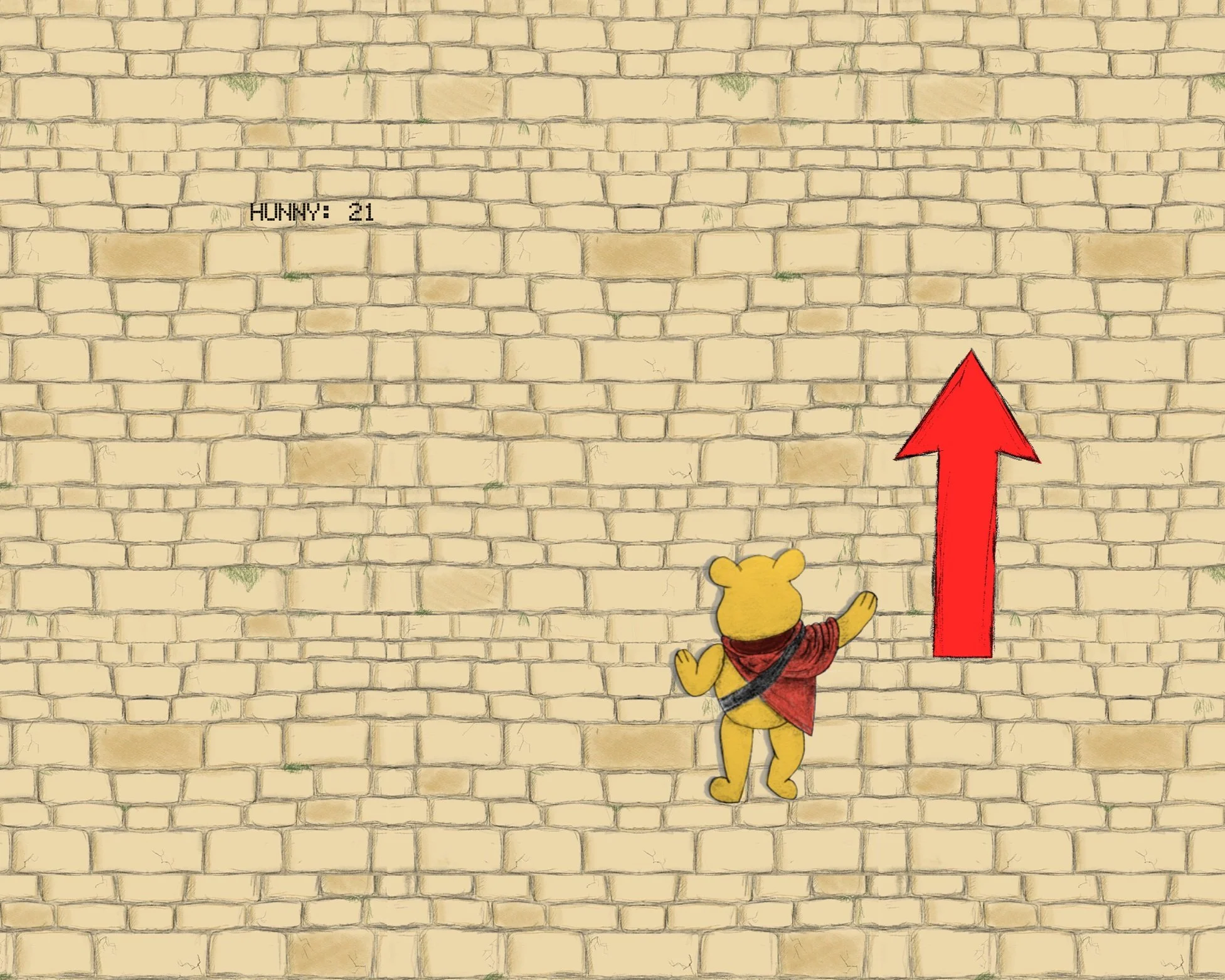

Chapter Xi: In wich

Pooh discovers censorship

How censorship influences your reality

Edward Bear, known to his friends as Winnie-the-Pooh, or Pooh for short, was feeling rather eleven o’clock-ish one day, and so he decided to look for some honey. Having wandered for quite a while, Pooh found himself walking through an unfamiliar part of the forest, when suddenly he stumbled upon a great big wall.

“The honey must surely be on the other side of this wall”, he thought, “for the only reason to build such a wall would be to hide something behind it. And since I can’t see any honey on this side, that must be what’s on …”

Pooh’s thoughts were interrupted by a rumbly sort of sound — for he was very hungry indeed. He then decided that the only way to the other side was to climb.

He climbed,

and he climbed,

and he climbed,

and he climbed.

Soon, however, Pooh found out all that climbing wasn’t as easy as he’d expected. Standing on top of that great big wall was an important man in an important suit. This man, called Xi Jinping, didn’t want any Pooh-bears behind his wall. The people behind the wall thought Pooh looked quite a lot like Xi and used this resemblance as a form of political satire, by making jokes on something called ‘the internet’. That would obviously undermine Xi’s authority to the other important men in important suits. As well as pollute the innocence of Pooh-bear with political euphemisms. So to prevent all that he made sure Pooh would never make it to the other side of the firewall.

“Winnie the Pooh blacklisted by China’s online censors

Social media ban for fictional bear follows comparisons with Xi Jinping”

(Yang, 2017)

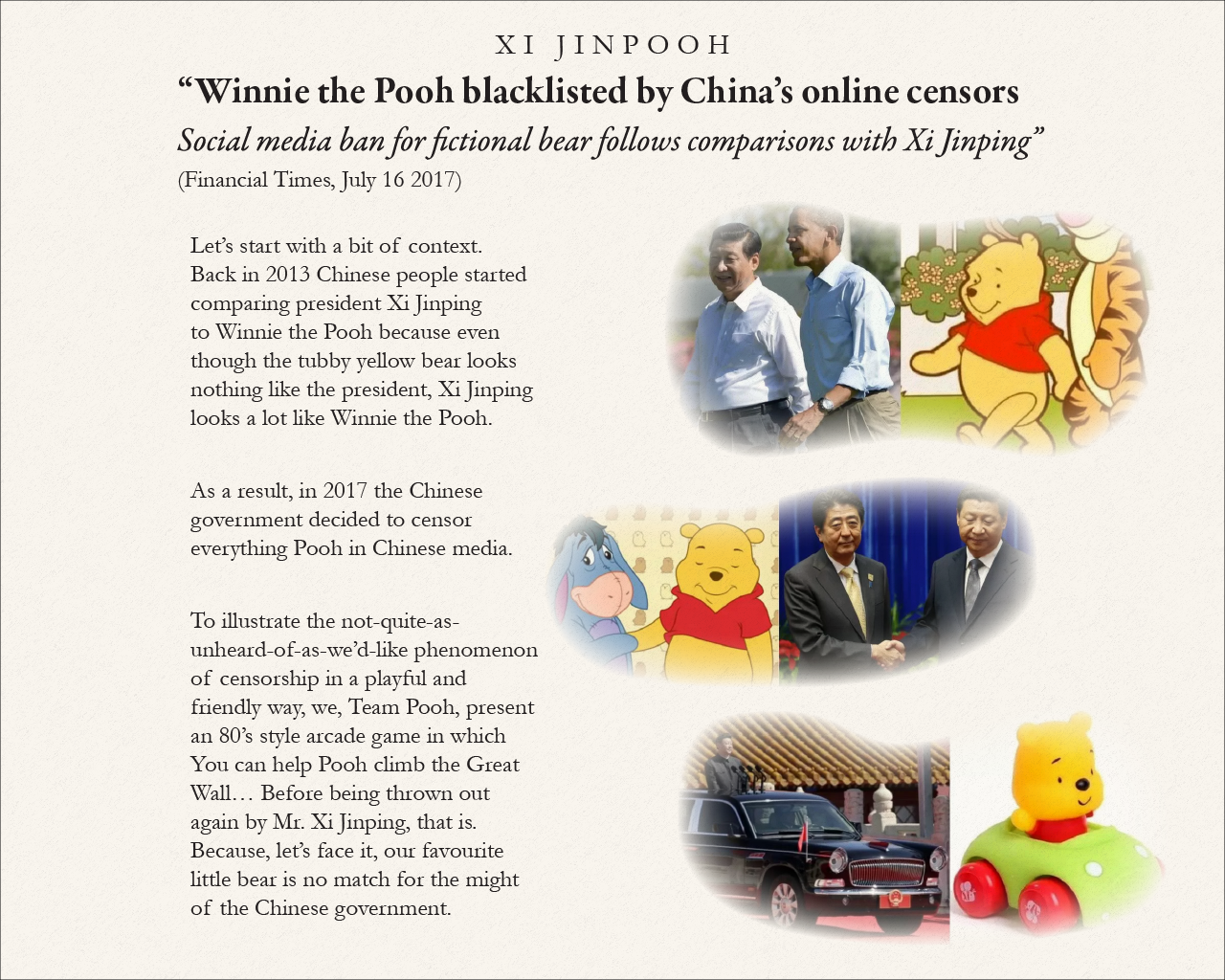

Let’s start with a bit of context. Back in 2013 Chinese people started comparing president Xi Jinping to Winnie the Pooh because even though the tubby yellow bear looks nothing like the president, Xi Jinping looks a lot like Winnie the Pooh.

“When Xi Jinping and Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe endured one of the more awkward handshakes in history netizens responded with Winnie the Pooh and Eeyore shaking hands.

And then there was the time President Xi popped his head out of the roof of his special Red Flag limousine to inspect the troops - a photo appeared online of a toy Winnie the Pooh popping out of his own little car.”

(McDonell, 2017)

As a result, in 2017 the Chinese government decided to censor everything Pooh in Chinese media.

To illustrate the not-quite-as-unheard-of-as-we’d-like phenomenon of censorship in a playful and friendly way, we, Team Pooh, present an 80’s style arcade game in which You can help Pooh climb the Great Wall… Before being thrown out again by Mr. Xi Jinping, that is. Because, let’s face it, our favourite little bear is no match for the might of the Chinese government.

The fact that a fictional character can be banned from a powerful, influential country is rather ridiculous interesting to think about. Winnie the Pooh is a source of positivity and joy, the embodiment of childlike innocence, yet the leader of a great big nation is threatened by this little yellow bear.

On Perception

What else is being censored? Are Chinese people missing out on the rest of the world? Perhaps not as dramatically as their Korean Neighbours where ol’ Kim* has ways of deleting any and all foreign or otherwise unapproved media from devices (King, 2019). But the banning of Facebook among other things must have great consequences on the Chinese world view (Barry, 2022). Can the Chinese be connected to reality if they don’t have all the information? Are they living in a different version of reality? Who says we’re given all the facts…

*(Dear Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un, Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Korea, Chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Supreme Commander of the Korean People’s Army)

(Reuters Staff, 2016)

Everyone has their own frame of reference; we decide which information we take in and how we perceive it. We al have our ideas, opinions, and assumptions which determine how we approach life. In today’s world this effect snowballs and gets blown out of proportion by the algorithm.

“Many choices that people consider their own are already determined by algorithms”

(Helbing & Pournaras, 2015).

We selectively pick the news we want to read about. Our supreme overlord the algorithm then notices our preferences and spews out new information based on those prior searches. This way it cuts fresh perspectives from our information diet, which results in your digital experience of the world being different from mine. Not by a lot, of course, or we’d notice. On larger scales, however, think nation wide or even globally, the differences are clearly there. (That’s how the world became a cradle for conspiracy theories, but that’s a different essay altogether.)

Social media greatly amplifies this selection issue effect. There is a huge amount of data to be found on apps and websites. It’s impossible for one mind to take it all in, which means we must choose. Every individual makes their own selection.

Of course, there are some overlapping trends and popular opinions but in the end your profile, with all the likes and follows, will offer different content than mine.

Does this mean we are all living in our own individual realities — never sharing the same reality as somebody else? Or do our little, solipsistic bubbles coexist and collide like an infinite, four-dimensional Venn-diagram? If so, there must be an over-arching Über-reality which nobody can truly see as result of trapped in a rabbit hole of individualism.

In his Critique of Pure Reason Immanuel Kant (1781) argues that the concept of perceiving an objective reality is flawed.

“Our perception of reality might start with sensations of something outside of ourselves, but by the time we perceive it our mind has organized, categorized and arranged those raw sensations into reality as it appears to us”

(Carreira, 2009).

On Fiction

How do we determine what’s real or fake? If a fictional character like Winnie-the-Pooh can have enough influence to be banned from a country; if the same rules which apply to people can be applied to fictional characters, are they still fictional? If characters have the same rights as humans, are they real or are we fake?

The world becomes a strange place if we don’t see the difference between fact and fiction anymore.

Perhaps a character feels so real because we humans experience emotional connections when watching movies, reading books, or consuming media in any of its forms. What we feel for a well-written, or plainly adorable character is just as, or often even stronger than the feelings we have for each other. In that moment they feel more real than anything else. And to you, they are.

You feel therefore they are!

It’s quite strange that we are capable of feeling emotions for a fictional story while knowing it’s just that; fictional. On the other hand, innocent stories like Pooh remind people of an unburdened, limitless world free from oppressive governments.

In a meeting on propaganda, ideology and culture chaired by Xi Jinping’s chief of staff Cai Qi hundreds of propaganda officials were urged to strengthen ‘Positive publicity’ in order to better guide public opinion.

(Zheng & Zheng, 2023)

Plato once said that well-written stories cause us to think irrationally and act according to our passions and urges. The Chinese government might have seen this behaviour as a threat to its own propagandistic outings. Because its own power is based on world building and storytelling, the one thing most capable of taking it down, is a story.

Stephen-vb Fotografie